After the 1885 Northwest Resistance (also known as the Northwest Rebellion), the federal government developed the pass system — a process by which Indigenous people had to present a travel document authorized by an Indian agent in order to leave and return to their reserves. The pass system was a way of controlling the movement of Indigenous people. It aimed to prevent large gatherings, seen by many White settlers as a threat to their settlements. Colonial officials also believed that the pass system would prevent another conflict like the Northwest Resistance. Used in conjunction with policies such as the Indian Act and residential schools, the pass system was part of an overall policy of assimilation. Though it never became a law, the pass system restricted Indigenous freedom in the Prairie West during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It has had lasting impacts on generations of Indigenous people, as restrictions on mobility caused damage to Indigenous economies, cultures and societies.

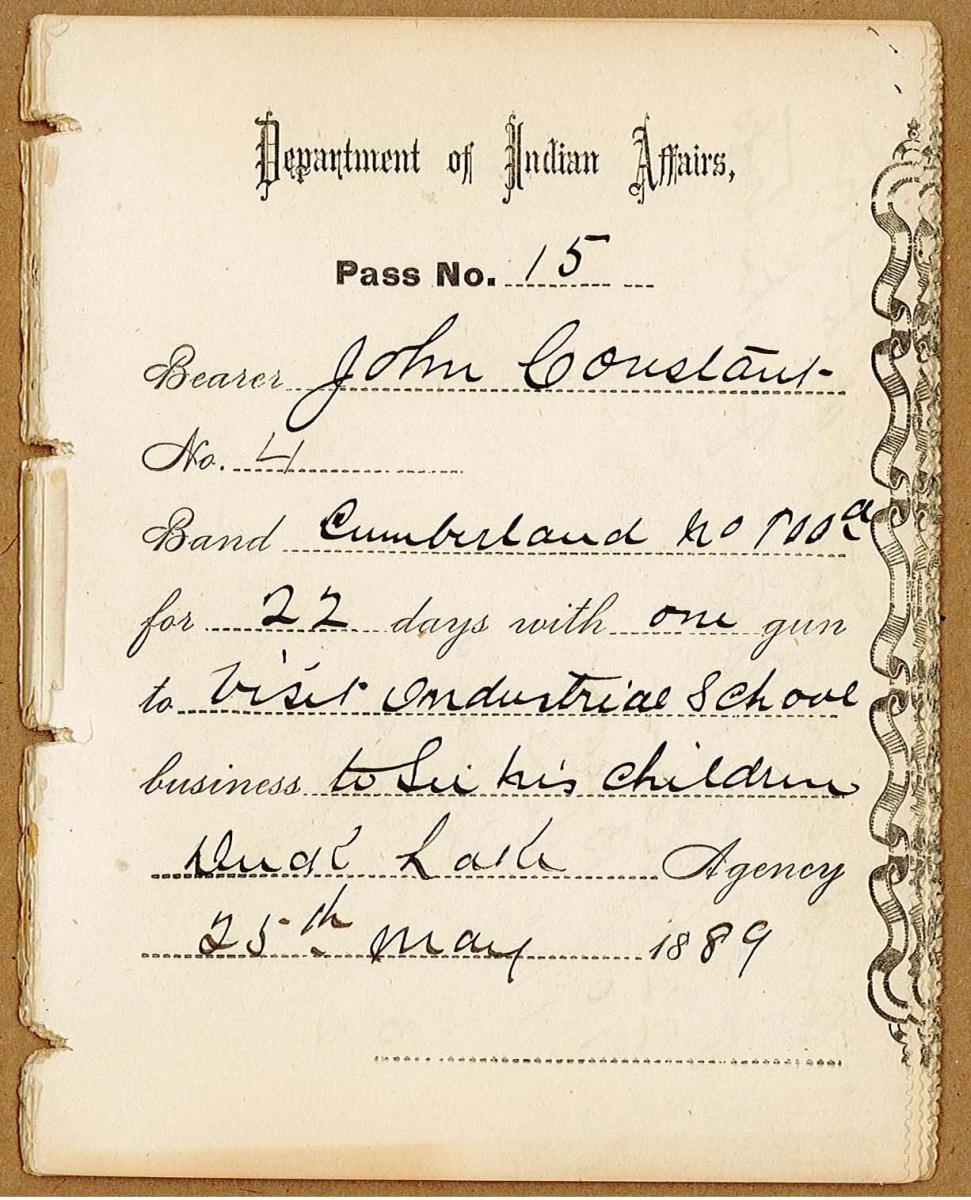

Stub from a reserve pass issued in Duck Lake Agency to John Constant who was traveling to visit his children at industrial school, 1889.

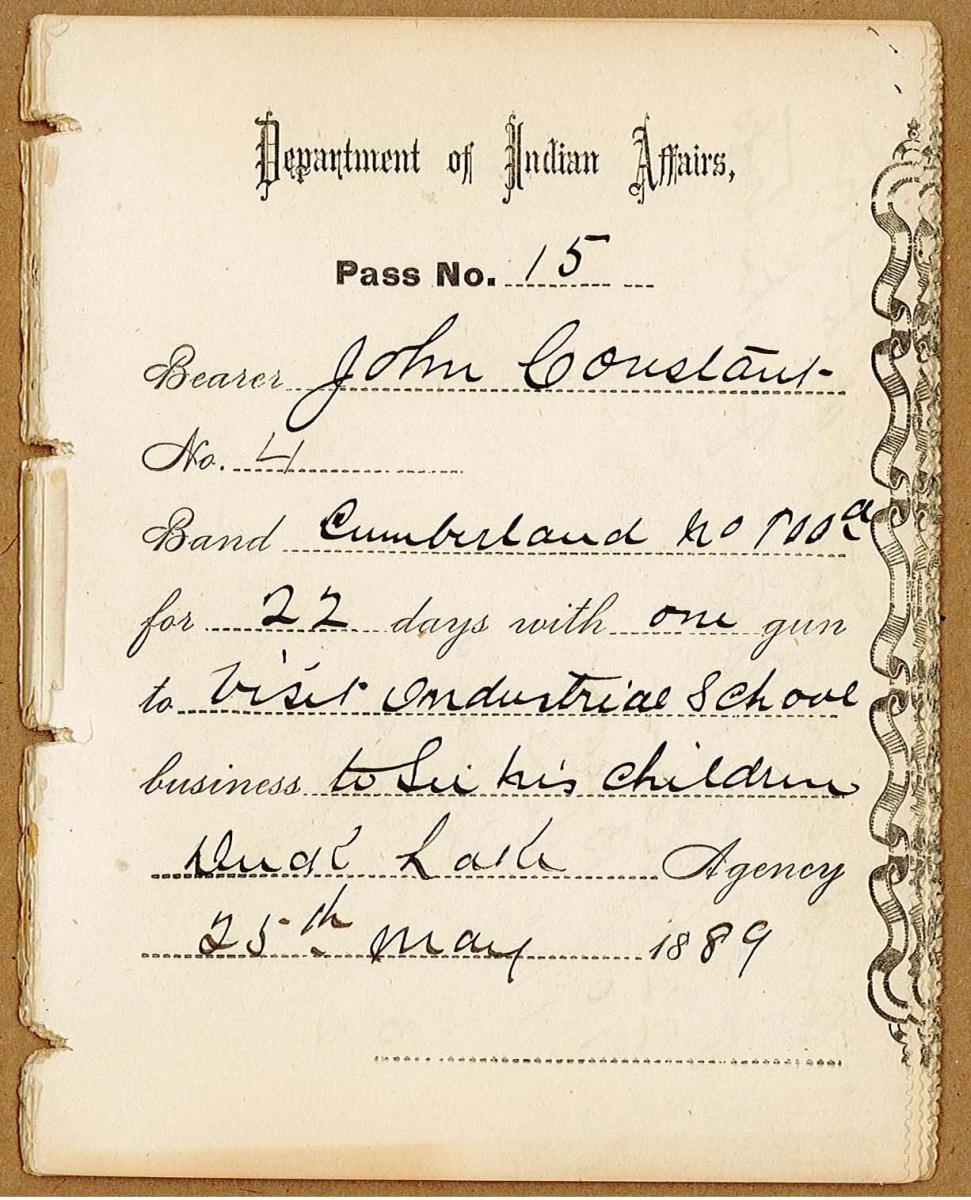

Stub from a reserve pass issued in Duck Lake Agency to Seepawpakao who was traveling to pick berries, 1889.

In the 1880s, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) used vagrancy laws to restrict the movement of Indigenous people. They feared Indigenous people might attack the United States army from Canada or that Indigenous people on both sides of the border might form an alliance

against the government. Colonial officials also believed that large congregations of Indigenous people threatened the peace and stability of White settlements in the West. Such large gatherings also allowed for the practice of Indigenous customs and religions, which were considered counterproductive to assimilation efforts. (See also Colonization.)

In 1882, the federal government passed an Order-in-Council that proposed authorities from both Canada and the United States grant permits to Indigenous people who wished to cross the border. In the same year, NWMP commissioner Acheson Gosford Irvine recommended that Indian agents — the administrators of Indigenous policy — prevent large groups from leaving their reserves.

By 1883, the federal department of Indian Affairs was also concerned about the movement of Indigenous women, in particular. Camped in tipis on the outskirts of White settlements — likely maintaining the home while the men were away — Indigenous women were considered threats to colonists. Deputy Superintendent General Lawrence Vankoughnet suggested a solution: Indian agents issue tipi owners a permit that would have to be produced if requested by the NWMP. Indian Commissioner Edgar Dewdney suggested the NWMP to use the Vagrant Act to remove individuals who camped without passes.

However, Commissioner Irvine of the NWMP argued in 1884 that a policy of confining Indigenous people to their reserves would be viewed as a breach of confidence. Indigenous people had signed various treaties with the Crown, many of which confirmed their right to hunt and travel freely. (See also Numbered Treaties.) Since there was no federally approved pass system at the time, the regulation of Indigenous movement was largely left up to the discretion of local authorities, such as Indian agents and the NWMP.

The Northwest Rebellion (or Northwest Resistance) of 1885 altered the government’s approach to Indigenous mobility. With a rebellion underway, federal officials sought a more clearly defined, wide-reaching policy of restricting Indigenous movement. In May 1885, Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton wrote to Indian Commissioner Edgar Dewdney suggesting colonial officials prevent Indigenous people from leaving their reserves, in the hopes of stopping them from joining the conflict. Dewdney responded, indicating that he did not have the authority to issue such a proclamation. Nevertheless, he told Indigenous people not to leave their reserves without permission. The idea of a formalized pass system was born.

In July 1885, a month after the conflict ended, Hayter Reed, assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs, penned a memo commonly known as the Memorandum on the Future Management of Indians, which influenced Indian policy of the time, and included what became the pass system. He submitted the memo to Dewdney, who approved of it. Dewdney then forwarded the memo to Vankoughnet, who forwarded it to John A. Macdonald — the Prime Minister and superintendent general of Indian Affairs at the time. However, Reed did not wait for the Macdonald’s response (which eventually came by way of Vankoughnet in October 1885) before implementing the pass system in August of that year. Reed admitted to Dewdney that he was aware this policy was not supported by any law, but that his actions were justifiable because they were for the greater good.

Although the Prime Minister endorsed the pass system, it was never enacted as a matter of law; rather, the system was accepted and applied for its perceived usefulness to colonizers. Such a system, Reed and his contemporaries believed, would prevent another rebellion and support a policy of assimilation. (See also Colonization.)

In 1886, various Indian agencies received books containing passes. In order for an Indigenous person to leave their reserve, they now needed a pass signed by the Indian agent, stating when they could leave, where they could go and when they had to return. Obtaining a permit was not an easy task. Depending on the size of the Indian agencies, and on the location of reserves, individuals would often have to travel long distances to the agent’s house to obtain a pass. There was no guarantee that the Indian agent would be present when they arrived or that they would approve the request. If the agent was away, there were few options beyond waiting or returning home. If a person left the reserve without permission and was caught by police, they would be arrested and brought back to their reserve.

Losing the freedom of unrestricted travel impacted various aspects of daily life. In terms of economics, restrictions on mobility limited what types of goods Indigenous farmers could sell at the market, and where they could sell their food. Sellers of produce required not only a pass to leave their reserve, but also a permit to sell that food. While the pass system regulated the mobility of people, the permit system — also used in the 1880s (until it was removed from the Indian Act in 1995) — regulated the sale of goods off reserves. Delays in getting passes and permits could result in the spoiling of produce and, therefore, a loss of income. Coupled with agricultural policies that typically valued White farmers over their Indigenous counterparts — for example, the Peasant Farm Policy (1889–97), which prohibited Indigenous farmers from using mechanized farm equipment, thereby limiting what they could produce — the pass and permit systems stifled agricultural potential and damaged Indigenous economies.

The pass system also prevented the practice of various cultural and spiritual activities by stopping people from travelling to participate in them. The pass system helped to enforce laws such as the Indian Act, which outlawed ceremonies like the potlatch and sun dance. While these traditions have survived to the modern day, the pass system and other policies of assimilation have worked to erode and, in some cases, to eradicate various aspects of Indigenous cultures.

Family life was similarly altered during this period. If family members did not live on the same reserve, travelling to see them became more difficult. The pass system also discouraged, and sometimes prevented, parents from visiting their children at residential schools. This has had intergenerational effects on families and communities, who were disconnected from one another for years. The pass system also segregated Indigenous people from non-Indigenous people in areas off of reserves, arguably contributing to feelings of mistrust as well as socioeconomic inequalities between the two groups.

Though some Indigenous people living under the pass system made attempts to resist their oppression, it was a difficult undertaking with potentially serious consequences. Indian agents held a lot of power over Indigenous communities, and many Indigenous people were therefore afraid of challenging the agents’ authority. Indigenous people also had little relative political power at the time; they were only able to become full citizens in 1960 — the same year Status Indian people could vote federally. (See also Indigenous Suffrage.)

On a number of occasions after 1886, the NWMP questioned the use of the pass system because it was not enforceable under law. In 1893, NWMP commissioner Lawrence Herchmer ordered members of the force to stop returning people without passes to the reserves. Hayter Reed disagreed with Herchmer, and ordered that the system continue to be enforced, even though he admitted again that there was no law compelling Indigenous people to remain on their reserves. Reed even suggested that officials keep this fact from Indigenous people for as long as they could. In a letter to the deputy superintendent general of Indian Affairs on 14 June 1893, Reed said:

If the Police are unable to do anything more than request Indians to return [to their reserves], then it will be better for them to abstain from doing that, since it will only draw the Indians’ notice to and emphasize the fact that [the Police] are powerless to enforce their requests…Had the order been kept quiet, the Indians might have remained for some time in ignorance, but as I have already seen references to it in the public press, no expectation of withholding it from them need now be entertained.

The pass system remained in effect in various locations and in various degrees of enforcement until it was phased out in the 1930s. There is some evidence to suggest that it was still being enforced into the early 1940s, in some isolated areas.

The pass system has had lasting effects on generations of Indigenous people. Over half a century of segregation and restrictions on mobility contributed to the loss of culture, strained family relations, caused feelings of distrust towards the government and police, and brought about socioeconomic inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities (as well as between reserve and off-reserve communities).

Until recently, few Canadians were aware the pass system existed; those who did were likely unaware of the fact that it was never a law. This may be attributed to the fact that recent research has shown the federal government made efforts to destroy any evidence of a pass system in Canada. In a post–Truth and Reconciliation era, the pass system highlights a dark and ignored part of Canadian history.

Efforts have been made to highlight oral histories about the pass system and bring the truth to light. In 2015, after an extensive five-year investigation, filmmaker Alex Williams released the documentary The Pass System, which explores the origins and implications of the system, as well as what it was like to live under it. Narrated by actor Tantoo Cardinal, the film was nominated for two Canadian Screen Awards.